| DATOS TÉCNICOS (MiG-19S) |

TECHNICAL DATA (MiG-19S) |

| TIPO: Avión de caza. | TYPE: Fighter aircraft. |

| TRIPULANTES: 1 | CREW: 1 |

| ENVERGADURA: 9 m. | SPAN: 29.6 ft. |

| LONGITUD: 12,54 m. | LENGTH: 41.2 ft. |

| ALTURA: 3,88 m. | HEIGHT: 12.9 ft. |

| SUPERFICIE ALAR: 25 m². | WING AREA: 270 ft². |

| PESO EN VACÍO: 5.172 kg. | EMPTY WEIGHT: 11,402 lb. |

| MOTOR: Dos motores turbojet Tumansky RD-9B de 31.8 kN (7,100 lbf) de empuje cada uno con posquemador. | ENGINE: Two Tumansky RD-9B afterburning turbojet engines providing 31.8 kN (7,100 lbf) thrust each with afterburner. |

ARMAMENTO:

|

ARMAMENT:

|

| VELOCIDAD MÁX.: 1.452 km/h a 10.000 m. | MAX. SPEED: 902 mph at 33,000 ft. |

| TECHO: 17.500 m. | CEILING: 57,400 ft. |

| ALCANCE: 1.390 km. | RANGE: 860 mi. |

| PRIMER VUELO: 24 de mayo de 1952. | FIRST FLIGHT: 24 May 1952. |

| VERSIONES: 23 | VERSIONS: 23 |

| CONSTRUIDOS: Unos 5.500 (Todos los modelos). | BUILT: Around 5,500 (All variants). |

Mientras el MiG-17 comenzaba a entrar en servicio en 1952, el MiG OKB comenzó a trabajar en serio en una próxima generación de cazas que pudieran alcanzar Mach 1 en vuelo nivelado. El primer intento, el «izdeliye M» o I-350, fue un avance audaz, con un ala con un barrido de 60 grados más superficies de cola con un barrido radical similar, y un nuevo motor turborreactor de flujo axial Lyulka TR-3A / AL-5. El I-350 debía conservar el armamento del MiG-15 y MiG-17, que constaba de un único cañón de 37 mm y dos cañones de 23 mm.

En ese momento, el MiG OKB también estaba trabajando en el «izdeliye SM-2» o caza de escolta de largo alcance I-360, cuyo desarrollo fue aprobado formalmente en agosto de 1951. El I-360 era efectivamente un nuevo avión propulsado por motores gemelos turborreactores AM-5F, cada uno de los cuales proporcionaba un empuje de postcombustión de 26,5 kN (2700 kgp / 5950 lbf) armados con un único cañón N-37D de 37 mm en cada raíz de ala. El armamento se cambió desde el morro hasta las raíces de las alas para reducir los problemas con la ingestión de gas del cañón en la entrada del motor, aunque complicó el mantenimiento en comparación con el MiG-15/17. El ala tenía un barrido de 60 grados; el avión presentaba una aleta ventral e, inicialmente, una disposición de cola en T.

Se construyeron dos prototipos de vuelo y un fuselaje de prueba estático. El primer vuelo del prototipo inicial del I-360 tuvo lugar el 24 de mayo de 1952, con el piloto de pruebas G.A. Sedov a los mandos. La máquina superó Mach 1 en vuelo nivelado el 25 de junio. El segundo prototipo realizó su vuelo inicial el 28 de septiembre. La disposición de la cola en T resultó insatisfactoria, perdiendo capacidad de control en ángulos de ataque altos, por lo que se instaló una disposición de cola convencional, con un plano de cola más grande instalado en la base de la aleta de cola en lugar de en la parte superior.

El rendimiento del I-360 fue bueno, pero el diseño adolecía de una serie de deficiencias claras. Aunque la VVS (Fuerza Aérea Roja) estaba entusiasmada con el modelo, los ingenieros de Mikoyan pensaron que podían hacerlo mejor y quisieron realizar un cambio importante, utilizando el nuevo turborreactor Mikulin AM-9B/RD-9B, esencialmente un AM-5F mejorado y ampliado de 25,5 kN (2600 kgp / 5730 lbf) de empuje seco y 31,9 kN (3250 kgp / 7165 lbf) de empuje de postcombustión. El nuevo diseño recibió la denominación de «izdeliye SM-9«.

A mediados de agosto de 1953, las autoridades concedieron el visto bueno formal para el desarrollo del SM-9, y se construirían tanto un caza táctico como un interceptor equipado con radar. Se construyeron tres prototipos del SM-9, realizándose el vuelo inicial del primer prototipo el 5 de febrero de 1954, nuevamente con Sedov a los controles. Las pruebas fueron bien, aunque se implementaron muchos cambios durante las pruebas de vuelo, y el tercer prototipo ya se aproximaba a las especificaciones de producción. Como era una práctica soviética común, se ordenó la producción del tipo como MiG-19 a mediados de febrero de 1954, mucho antes de que se completaran las pruebas, mientras la VVS esperaba con ansias su primer auténtico caza supersónico.

Los dos primeros MiG-19 de producción se entregaron a la VVS en junio de 1955, realizando 48 de ellos un sobrevuelo en el espectáculo aéreo de Tushino en agosto. La OTAN asignó al MiG-19 el nombre clave de «Farmer«.

La producción inicial del MiG-19 se fabricó principalmente con una aleación de aluminio para aviones. Tenía alas montadas en el medio fuertemente curvadas; una cola en flecha convencional con un filete caudal delantero y una aleta ventral debajo de la cola. La disposición de la superficie de control era convencional, con un solo flap debajo de cada ala dentro de un alambrado en las alas prominente y alerones exteriores. La cola presentaba timón y elevadores convencionales. Había dos frenos de inmersión debajo del fuselaje, detrás del ala. Todo el combustible interno iba en cuatro depósitos en el fuselaje, ya que la delgadez de las alas impedía su instalación. El fuselaje trasero podría retirarse justo detrás de las raíces de las alas para el mantenimiento de los turborreactores gemelos RD-9B.

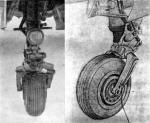

El tren de aterrizaje de triciclo tenía ruedas simples. El tren de morro se plegaba hacia adelante y el tren principal estaba articulado en las alas para retraerse hacia el fuselaje. Había un pequeño parachoques de goma justo detrás de la aleta ventral para proteger la cola durante el despegue. Debajo de la cola se guardaba un paracaídas de freno.

El armamento consistía en tres cañones NR-23 de 23 mm, uno en la parte inferior derecha del morro y otro en cada raíz del ala. Había un pequeño panel a cada lado del fuselaje para proteger el avión de los fogonazos del cañón situado en la raíz del ala, aunque parece que este panel no se incluyó en toda la producción. Había un soporte debajo del centro de cada ala que podía usarse para transportar bombas o lanzacohetes pero, por lo que muestra la evidencia fotográfica, generalmente llevaba un depósito externo de 760 litros. Se podrían instalar dos pilones en cada ala para transportar cápsulas de cohetes no guiados, lo que proporciona una carga externa típica para una misión de ataque terrestre de dos depósitos externos y cuatro cápsulas de cohetes.

El piloto iba sentado en un asiento eyectable bajo una cubierta que se deslizaba hacia atrás. La cabina presentaba blindaje y un parabrisas blindado. La aviónica estándar incluía radios, IFF, brújula giromagnética, radiogoniómetro automático, sistema de aterrizaje por instrumentos, mira asistida por radar y un sistema de alerta de radar Sirena-2 RWR. Una característica interesante era la sonda Pitot de punta larga instalada en el labio inferior de la entrada del motor, articulada hacia arriba en el suelo para evitar accidentes en tierra.

El rendimiento del MiG-19 resultó excelente, y fuentes rusas afirmaron que tenía ventaja en casi todos los aspectos sobre su rival contemporáneo, el F-100 Super Sabre norteamericano. Sin embargo, el MiG-19 no tuvo un buen comienzo entre los pilotos de la Fuerza Aérea Roja, ya que tenía una desafortunada tendencia a explotar en el aire. El problema finalmente se atribuyó a un depósito de combustible colocado debajo de los motores que podía estallar cuando los motores se sobrecalentaban. Se insertó un escudo térmico, pero los pilotos no estaban contentos con el manejo del MiG-19. Aterrizaba demasiado «caliente»; tenía una desagradable tendencia a cabecear cuando se activaban los aerofrenos y era difícil de mantener recto a altas velocidades.

Muchas de estas deficiencias se habían reconocido durante las pruebas de vuelo, pero como el avión se había apresurado a entrar en producción antes de que se completaran las pruebas, tuvieron que repararse en servicio. Una versión mejorada del caza, el MiG-19S, se introdujo en la fabricación en 1956. La OTAN lo denominó Farmer-C.

El MiG-19S presentaba modificaciones, particularmente en un filete de aleta trasera más grande para mejorar la estabilidad direccional, un plano de cola totalmente móvil, con pequeños pesos anti-vibración en las puntas que le daban una apariencia de púas distintiva, un tercer aerofreno ventral justo detrás de la aleta ventral, y una serie de pequeñas modificaciones aerodinámicas. Hubo algunas mejoras en aviónica, incluida una nueva radio, un radar de alcance de mira mejorado y un receptor de sistema de navegación aérea de largo alcance «Svod» (Cúpula). Aunque la producción inicial del MiG-19S conservó los tres cañones NR-23, la mayoría se construyó con tres cañones NR-30 de 30 mm mucho más potentes y con frenos de boca. Se instalaron paneles protectores más grandes a los lados del fuselaje para proteger el avión de los efectos del cañón del ala.

Los pilotos todavía no estaban muy contentos con el MiG-19S, ya que era propenso a sufrir fallos hidráulicos e incendios durante el vuelo. Por lo general, estos se debían a defectos de fabricación y no de diseño, pero tardaron algún tiempo en resolverse y el avión conservó su mala reputación entre los pilotos.

Se construyó una pequeña cantidad de MiG-19S en una configuración de reconocimiento, con el cañón del fuselaje reemplazado por una cámara. Estos aviones recibieron la designación de MiG-19R y presentaban motores RD-9BF-1 mejorados, con aproximadamente un 10% más de empuje en seco y un sistema de poscombustión mejorado. Los cazas MiG-19S de última producción también se construyeron con motores RD-9BF-1 y se denominaron MiG-19SF.

Como se ha mencionado, el visto bueno al desarrollo del MiG-19 también especificaba el diseño de un interceptor equipado con radar, trabajo que avanzó en paralelo con el desarrollo de la variante de caza táctico. El primero de los tres prototipos SM-7 de la variante interceptora realizó su vuelo inicial el 28 de agosto de 1954 con V. A. Nefyodov a los mandos.

El SM-7 presentaba cambios en el morro más largo, que alojaba el radar RP-1 Izumrud, y el cañón de 23 mm del fuselaje eliminado, manteniéndose los cañones en las dos alas. Al igual que en el MiG-17P/PF, el Izumrud se componía un radar de búsqueda en un radomo de labios gruesos y un radar de seguimiento en un radomo en el mamparo de entrada. El tubo pitot se reubicó en la punta del ala derecha. La cabina era más grande para acomodar los sistemas de control y visualización del radar. Después de las pruebas, la variante del interceptor entró en producción en 1955 como MiG-19P y entró en servicio principalmente con las PVO (Fuerzas de la Defensa Aérea), aunque la VVS e incluso la Armada Roja operaron varios de ellos. La OTAN lo nombró Farmer-B.

Aparte del nuevo morro del radar, la cabina revisada y la eliminación del cañón del fuselaje, el MiG-19P era similar al MiG-19S, con el largo filete de aleta de cola y el plano de cola con todas sus superficies móviles. Era un poco más lento que el MiG-19S y el rendimiento sufrió ligeramente. Los pilotos soviéticos en general estaban aún menos contentos con el MiG-19P, no sólo por la ligera degradación en el rendimiento, sino también porque la vista desde la cabina equipada con radar era sustancialmente peor, y debido a la falta de fiabilidad del radar.

Los MiG-19P de producción inicial tenían cañones NR-23, pero posteriormente se instaló el cañón NR-30. Los Farmer-B a menudo llevaban un único lanzador de cohetes no guiados debajo de cada ala para ataques aire-aire. Al final de su vida útil, algunos MiG-19P fueron modificados para llevar el misil AAM K-13/AA-2 Atoll, copia del Sidewinder, en un nuevo pilón externo. Las últimas máquinas de producción llevaban el radar RP-5 Izumrud mejorado, con mayor alcance y mejor fiabilidad. Varios MiG-19P estaban equipados con el enlace de datos de control terrestre Gorizont-1, empleados como guía para dirigir un caza a su objetivo y se denominaron MiG-19PG.

Los misiles aire-aire (AAM) eran considerados el futuro del combate aéreo a mediados de la década de 1950, y en 1956 se comenzó a trabajar en una variante del MiG-19P armada con misiles. Dos de los prototipos del MiG-19P fueron modificados para pruebas y la nueva variante entró en servicio en 1957 como MiG-19PM. A la variante se le asignó el nombre de informe de la OTAN de Farmer-E.

El MiG-19PM era muy similar al MiG-19P, excepto que se eliminó el armamento del cañón, para ser reemplazado por cuatro misiles K-5M/RS-2/AA-1. El radar RP-1 Izumrud se actualizó a la variante PR-2U, que proporcionaba capacidades de control para los AAM. El MiG-19PM era incluso más desagradable que el MiG-19P, ya que los misiles reducían sustancialmente el rendimiento y los K-5M no eran nada del otro mundo como armamento.

Algunos MiG-19P fueron modificados al estándar MiG-19PM, aunque estos aviones sólo podían transportar dos misiles. Varios MiG-19PM fueron equipados con el enlace de datos de control terrestre «Lazur» (Azul de Prusia) en la década de 1960. Estas máquinas modificadas fueron designadas MiG-19PML.

Los intentos estadounidenses de utilizar globos para espiar a la URSS llevaron al Kremlin a encargar al OKB Mikoyan el desarrollo de una variante del MiG-19 que pudiera derribar los globos. El trabajo inicial se centró en un MiG-19S más ligero con armamento reducido, sin blindaje de cabina, etc., equipado con motores RD-9BF mejorados. El avión se puso en producción limitada en 1956 como MiG-19SV, uno de ellos pilotado por N. I. Korovushkin logró un récord mundial de altitud de 20.740 m el 6 de diciembre de 1956.

Para entonces, Estados Unidos había obtenido una plataforma de reconocimiento mucho mejor que los globos, el avión espía Lockheed U-2, que podía volar sobre la URSS a altitudes fuera del alcance de cualquier caza soviético, incluido el MiG-19SV. El primer sobrevuelo de la URSS por un U-2 fue el 4 de julio de 1956, Día de la Independencia de Estados Unidos, como si se burlara de los soviéticos, aunque en realidad los estadounidenses se sorprendieron cuando los radares soviéticos detectaron al aparato, pues se creía que el U-2 sería efectivamente invisible a su altitud para los radares que poseían los soviéticos. Derribar el U-2 era una alta prioridad, por lo que el OKB de Mikoyan investigó cómo equipar al MiG-19S con un propulsor de combustible líquido. El resultado fue el MiG-19SU.

El propulsor de combustible líquido se llevaba en forma de mochila en la zona ventral vientre. La distancia al suelo era estrecha y, por lo tanto, la rotación de despegue tenía que ser superficial. El paquete era autónomo y solo requería conexiones eléctricas y mecánicas al avión, pero se necesitaba algún refuerzo de la estructura del avión para soportar las tensiones de empuje. El cohete funcionó bien hasta ese punto, pero los propulsores líquidos almacenables por regla general son corrosivos y tóxicos, y el combustible almacenable y el oxidante generalmente tienen la característica de arder espontáneamente cuando se mezclan. Eso hizo que manejar el cohete fuera algo problemático y peligroso.

De hecho, el MiG-19SU podría alcanzar la altitud operativa de un U-2, el problema era que realmente no podía hacer mucho. A tales altitudes, incluso el U-2, con sus alas de planeador y su estructura ligera, era apenas aerodinámico, al borde de entrar en pérdida, y sólo los mejores pilotos podían volarlo. El MiG-19SU era tan aerodinámico y controlable como un ladrillo una vez que alcanzaba tales altitudes, y era probable que los turborreactores se incendiaran en el aire. Todo lo que un piloto soviético podía hacer era básicamente dar un salto corriendo hacia un U-2 desde una altitud más baja, y esperar poder conseguir algunos disparos antes de que el caza alcanzara la cima de su arco y cayera de nuevo.

También se construyeron varios MiG-19P para transportar el paquete de cohetes, y se denominaron MiG-19PU. No fueron más efectivos, y la verdadera respuesta al U-2 fue el nuevo misil SAM S-75 Tunguska (OTAN SA-2) de gran altitud. Los SA-2 finalmente derribaron un U-2 en la fecha apropiada, el 1 de mayo de 1960, y el piloto, el agente de la CIA Francis Gary Powers, fue capturado. El presidente estadounidense Dwight Eisenhower, que siempre había tenido dudas sobre los sobrevuelos, los canceló definitivamente.

Los checos construyeron una cantidad relativamente pequeña de cazas diurnos MiG-19S en la planta de Vodochody entre 1958 y 1961, denominados Avia S-105. En realidad, sólo los fuselajes fueron construidos por los checos, ya que los motores y otros equipos eran importados de la URSS. Toda la producción del S-105 fue empleada por Checoslovaquia.

Los chinos también recibieron el MiG-19 de manos de los soviéticos, pero tuvieron un comienzo lento. Los esfuerzos iniciales de producción con licencia se centraron en el interceptor MiG-19P. La fábrica de Shenyang obtuvo equipos desmontados del avión de la URSS en 1958, y el primer aparato ensamblado en China voló en diciembre de ese año. El primer MiG-19P o J-6 construido en Shenyang voló en septiembre de 1959.

La fábrica de Nanchang también trabajó en el montaje y producción del MiG-19PM en paralelo, y el avión se designó J-6B, pero todo el esfuerzo en ambas fábricas fracasó durante el período conocido como «Gran Salto Adelante» que fue impulsado por la retórica revolucionaria en lugar de la planificación industrial racional. Los resultados fueron un fiasco, con programas poco realistas hasta que todos colapsaron en el caos.

Después del colapso, la industria china se recuperó y empezó de nuevo. El trabajo de producción con licencia del caza diurno MiG-19S en la fábrica de Shenyang comenzó en 1961, y los primeros aviones construidos en China volaron a finales de ese año. Conservaron la designación J-6.

La producción comenzó a aumentar en los años siguientes, a pesar de que las relaciones entre China y la URSS se deterioraron tanto a principios de la década de 1960 que los soviéticos les retiraron toda su asistencia técnica. Desafortunadamente, justo cuando la producción estaba avanzando a mediados de la década, China entró en otro período de confusión, esta vez causado por la «Gran Revolución Cultural Proletaria» de Mao Zedong.

La producción del MiG-19S/J-6 logró sobrevivir y en la década de 1970 volvió a aumentar. En ese momento era básicamente un avión obsoleto, pero por el momento los chinos no tenían la experiencia para construir uno mejor y las relaciones con la URSS seguían frías. La fábrica de Shenyang construyó alrededor de 3.000 cazas J-6 en la década de 1980, y un gran número se exportó con la designación de F-6 a estados clientes chinos, particularmente Pakistán.

La variante más distintiva construida en China fue el entrenador JJ-6, conocido como FT-6 para el mercado de exportación. A medida que el J-6 se convirtió en el caza diurno estándar de la Fuerza Aérea del Ejército Popular de Liberación (PLAAF), el JJ-5 derivado del MiG-17 se volvió cada vez más inadecuado, por lo que se trabajó para diseñar una variante con asiento tándem del J-6C. como entrenador avanzado supersónico. Era estrictamente un avión chino ya que formalmente nunca hubo un MiG-19UTI.

El fuselaje se estiró 84 cm por delante de las alas para dar cabida a la cabina con asientos en tándem, que presentaba cubiertas gemelas que se abrían con bisagras hacia la derecha. Se eliminaron los cañones del ala, pero generalmente se conservó el cañón del fuselaje; la única aleta ventral se cambió por aletas gemelas.

Pakistán recibió un buen número de entrenadores FT-6 y en la década de 1980 creó una instalación con ayuda china para repararlos. Los paquistaníes equiparon sus F-6 y FT-6 con asientos eyectables cero-cero impulsados por cohetes Martin Baker Mark 10L. Los asientos Martin Baker no sólo mejoraron la seguridad, sino que también tenían un perfil más bajo y proporcionaban más espacio para la cabeza en la cabina. Otra innovación paquistaní fue la instalación de misiles AAM AIM-9 Sidewinder fabricados en Estados Unidos en los soportes exteriores del ala. Existen fotografías del F-6 con este armamento. No está claro si el FT-6 alguna vez estuvo equipado de manera similar.

El F-6 ya no se produce, si bien parece permanecer en servicio con los estados clientes chinos, los monoplazas chinos en su mayoría se han convertido en drones, no sólo drones de entrenamiento, sino también drones de ataque, capaces de realizar ataques aéreos.

El servicio del MiG-19 en la URSS fue transitorio y poco significativo. La mayor acción que vieron fue contra aviones espías occidentales que exploraban alrededor o dentro de las fronteras de la URSS. Posiblemente uno de los encuentros más conocidos tuvo lugar el 1 de junio de 1960, cuando cazas MiG-19 derribaron un avión de reconocimiento electrónico Boeing RB-47H que estaba husmeando alrededor de Archangel en el norte, donde cuatro miembros de la tripulación resultaron muertos y dos hechos prisioneros. El RB-47H estaba en el espacio aéreo internacional, pero los soviéticos estaban molestos por las incursiones del U-2 y otras invasiones sobre su territorio y querían enviar un mensaje al presidente Eisenhower; Los dos prisioneros fueron liberados después de que Eisenhower dejara la presidencia. Hubo otros derribos del MiG-19 hasta bien entrada la década.

El modelo quedó fuera del servicio de primera línea con la VVS y las PVO a finales de los años 1960, aunque permaneció en servicio secundario hasta bien entrados los años 1970. Aunque quedara fuera de servicio en la URSSS, todavía era un pilar para los chinos rojos y participó en algunos combates. Los aviones taiwaneses eran adversarios comunes. Hubo una gran batalla aérea entre las fuerzas rojas y nacionalistas chinas en 1967, cuando doce J-6 se enfrentaron a cuatro Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. Los MiG se llevaron la peor parte, con dos pérdidas y ningún derribo.

También hay relatos de J-6 chinos que realizaron misiones de combate durante las poco frecuentes disputas fronterizas con los soviéticos, aunque sin registros de combates aéreos, y de encuentros durante la Guerra de Vietnam con aviones estadounidenses que se desviaron hacia el espacio aéreo chino. Estos enfrentamientos causaron algunos derribos de estadounidenses y, al parecer, ninguna pérdida de aviones chinos, aunque los MiG a veces tuvieron que retirarse apresuradamente al espacio aéreo chino cuando los estadounidenses pidieron refuerzos.

Los F-6 fueron suministrados a Vietnam del Norte al final de la guerra, aunque el modelo no vio mucha acción en comparación con el MiG-21 y particularmente con el MiG-17. Los F-6 norvietnamitas realizaron algunos combates aéreos en 1972, el último año de la guerra aérea real. Resultó más ágil que el MiG-21, y con mejor rendimiento que el MiG-17.

El MiG-19 participó en algunos combates en el Medio Oriente: Egipto obtuvo su primer lote en 1958 y Siria recibió el modelo a partir de 1962. Los MiG-19 egipcios participaron en algunas acciones de ataque terrestre en apoyo de las fuerzas revolucionarias durante la guerra civil en Yemen a principios de la década de los años 1960. El primer combate aéreo del que se tuvo noticia en Oriente Medio con el MiG-19 fue el 29 de noviembre de 1966, cuando dos cazas MiG-19 egipcios se enfrentaron a dos Mirage IIIC israelíes. Los israelíes reclamaron dos derribos y ninguna pérdida.

Muchos MiG-19 estuvieron en servicio en Egipto y Siria durante la Guerra de los Seis Días en 1967, pero la mayoría fueron destruidos en tierra, y los que sobrevivieron fueron derribados por la superioridad aérea israelí. A pesar de la competencia desigual, los pilotos israelíes consideraron que el MiG-19 era un adversario potencialmente peligroso debido a su rendimiento, maniobrabilidad y armamento pesado.

Los iraquíes obtuvieron algunos cazas MiG-19S a principios de la década de 1960, pero luego los vendieron. Algunos vieron acciones contra los kurdos en la década de los años 1970. En 1983, durante la guerra Irán-Irak, los iraquíes obtuvieron un lote de F-6 a través de Egipto, mientras que los iraníes adquirieron un lote de F-6 chinos. Ninguno de los bandos los utilizó mucho durante el conflicto y no hay registros de combates entre MiG.

El combate más importante del MiG-19 sucedió durante la Guerra Indo-Pakistán en diciembre de 1971. Los paquistaníes afirmaron que sus F-6 derribaron unos diez aviones indios, con una pérdida de cuatro F-6. Por supuesto, los indios sostienen que las reclamaciones paquistaníes por los derribos están infladas y que el número de pérdidas está subestimado. En cualquier caso, los paquistaníes consideraron que el F-6 se había comportado bien y ampliaron su flota. Durante la guerra de Afganistán, los F-6 paquistaníes lucharían para hacer frente a las incursiones de aviones soviéticos y afganos en el espacio aéreo paquistaní. Los intrusos a menudo perseguían a guerrilleros mujaidines que intentaban escapar a sus santuarios en Pakistán. Como era un secreto a voces que los paquistaníes apoyaban a los muyahidines, a veces los intrusos no tenían ganas de irse cuando eran desafiados, y hay relatos de grandes combates aéreos. Los paquistaníes no retiraron el F-6 hasta 2002.

El F-6 fue suministrado a varias naciones africanas. Tanzania voló este modelo contra Uganda durante la guerra entre los dos estados en 1978 y 1979, mientras que Sudán lo utilizó contra los separatistas en el sur de Sudán, con al menos uno derribado. Los somalíes volaron el F-6 contra los rebeldes y los etíopes en los años 1980, aunque con la ruptura del orden civil en Somalia todos sus aviones terminaron abandonados a principios de los años 1990.

Even as the MiG-17 was going into service, the MiG OKB began to work in earnest on a next generation of fighters that could attain Mach 1 in level flight. The first attempt, the «izdeliye M» or I-350, was a bold move forward, featuring a wing with a sweepback of 60 degrees plus tail surfaces with a similar radical sweepback, and a new Lyulka TR-3A / AL-5 axial flow turbojet engine. The I-350 was to retain the armament of the MiG-15 and MiG-17, consisting of a single 37mm cannon and two 23mm cannon.

At the time, the MiG OKB was also working on the «izdeliye SM-2» or I-360 long-range escort fighter, with development formally approved in August 1951. The I-360 was effectively a new aircraft which was powered by twin AM-5F turbojets, each providing an afterburning thrust of 26.5 kN (2,700 kgp / 5,950 lbf), and armed with a single N-37D 37mm cannon in each wing root. The armament was moved from the nose to the wingroots to reduce problems with engine intake gun gas ingestion, though it complicated maintenance compared to the neat cannon tray of the MiG-15/17. The wing had a leading-edge sweep of 60 degrees; the aircraft featured a ventral fin and, initially, a tee tail arrangement.

Two flight prototypes and a static test airframe were built. First flight of the initial I-360 prototype was on 24 May 1952, with test pilot G.A. Sedov at the controls; the machine broke Mach 1 in level flight on 25 June. The second prototype performed its initial flight on 28 September. The tee tail arrangement proved unsatisfactory, losing control authority at high angles of attack, and so a conventional tail arrangement was fitted, with a larger tailplane fitted at the base of the tailfin instead of the top.

Performance of the I-360 was good, but the design suffered from a number of clear deficiencies. Although the VVS (Red Air Force) was enthusiastic about fielding the type, Mikoyan engineers thought they could do better and wanted to perform a major redesign, using the new Mikulin AM-9B / RD-9B turbojet, essentially an improved and scaled-up AM-5F with 25.5 kN (2,600 kgp / 5,730 lbf) dry thrust and 31.9 kN (3,250 kgp / 7,165 lbf) afterburning thrust. The new design was given the designation of «izdeliye SM-9«.

A formal go-ahead for the development of the SM-9 was granted by the authorities in mid-August 1953, with both a tactical fighter and a radar-equipped interceptor to be built. Three SM-9 prototypes were built, with the initial flight of the first prototype on 5 February 1954, again with Sedov at the controls. Trials went well, though many changes were implemented during flight tests, with the third prototype approximating production specification. As was common Soviet practice, the type was ordered into production as the MiG-19 in mid-February 1954, well before the trials were completed, with the VVS looking forward to the service’s first true supersonic fighter.

The first two production MiG-19s were delivered to the VVS in June 1955, with 48 of the machines performing a flyover at the Tushino air show in August. NATO assigned the MiG-19 the reporting name «Farmer«.

The initial production MiG-19 was made mostly of aircraft aluminum alloy. It had strongly swept mid-mounted wings; a conventional swept tail assembly with a forward tailfin fillet; and a ventral fin under the tail. The control surface arrangement was conventional, with a single flap under each wing inboard of a prominent wing fence and outboard ailerons. The tail featured conventional rudder and elevators. There were twin dive brakes under the fuselage behind the wing. All internal fuel was carried in four fuselage tanks; there was no room for tanks in the thin wing. The rear fuselage could be pulled off just aft of the wingroots to expose the twin RD-9B turbojets for servicing.

All assemblies of the tricycle landing gear had single wheels, with the nose gear retracting forward and the main gear hinging in the wings to retract towards the fuselage. There was a small rubber bumper just aft of the ventral fin to protect the tail in case of «over-rotation» on take-off. A brake parachute was stored under the tail.

Built-in armament consisted of three NR-23 23mm cannon, one in the right underside of the nose and one in each wing root. There was a small blast panel on each side of the fuselage to protect the aircraft from the muzzle blast of the wingroot cannon, though it seems that this panel was not included on all production. There was a stores pylon under the middle of each wing that could be used to carry bombs or rocket pods but, as far as the photographic evidence shows, usually carried a 760-liter (200 US gallon) external tank. Two pylons could be fitted inboard of the external tank pylon on each wing for carriage of unguided rocket pods, giving a typical external load for a ground attack mission of two external tanks and four rocket pods.

The pilot sat on an ejection seat under a rearward-sliding canopy. The cockpit featured armor plating and an armor glass windscreen. Standard avionics included radios, IFF, gyromagnetic compass, radio automatic direction finder, instrument landing system, radar-assisted gunsight, and a Sirena-2 RWR. One interesting feature was the long nose pitot probe fitted to the bottom lip of the engine intake, with the probe hinging upward on the ground so people wouldn’t walk into it.

The MiG-19’s performance was excellent, with Russian sources claiming it had the edge in almost all respects over its contemporary rival, the US North American F-100 Super Sabre. However, the MiG-19 didn’t get off to a good start with Red Air Force pilots, since it had an unfortunate tendency to explode in mid-air. The problem was finally traced to a fuel tank placed under the engines that could cook up when the engines overheated. A heat shield was inserted, but pilots remained unhappy with the MiG-19’s handling. It landed too «hot»; had a nasty tendency to pitch up when the airbrakes were deployed; and was a beast to keep flying straight at high speeds.

Many of these deficiencies had been recognized during flight trials, but since the aircraft had been rushed into production before testing was complete, they had to be fixed in service. An improved version of the fighter, the definitive MiG-19S, was introduced into manufacturing in 1956. It was given the NATO reporting name of Farmer-C.

The MiG-19S featured tweaks overall, particularly in the form of a larger tailfin fillet to improve directional stability; an all moving slab tailplane, with small anti-flutter weights on the tips that gave it a distinctive barbed appearance; a third ventral airbrake just behind the ventral fin; and a range of small aerodynamic modifications. There were a few avionics improvements, including a new radio, improved gunsight ranging radar, and a «Svod» (Dome) long-range air navigation system receiver. Although early MiG-19S production retained the three NR-23 cannon, most were built with three much more formidable NR-30 30mm cannon with muzzle brakes. Larger blast panels were fitted to the sides of the fuselage to protect the aircraft from the muzzle blast of the wing cannon.

Pilots were still not very happy with the MiG-19S, since it was prone to hydraulic failures and inflight fires. These were generally due to manufacturing and not design defects, but they took some time to work out, and the type retained its bad reputation among pilots.

A small number of MiG-19S machines were built in a reconnaissance configuration, with the fuselage cannon replaced by a camera payload. These aircraft were given the designation of MiG-19R and featured uprated RD-9BF-1 engines, with about 10% more dry thrust and an improved afterburner system. Late-production MiG-19S fighters were also built with RD-9BF-1 engines, with these aircraft designated MiG-19SF.

As mentioned, the development go-ahead for the MiG-19 also specified the design of a radar-equipped interceptor variant, work proceeding in parallel with development of the tactical fighter variant. The first of three SM-7 prototypes of the interceptor variant performed its initial flight on 28 August 1954, with V.A. Nefyodov at the controls.

The SM-7 featured a redesigned and longer nose with RP-1 Izumrud radar and the fuselage 23mm cannon deleted, the two wing cannon being retained. As with the MiG-17P/PF, the Izumrud featured a search radar in a fat lip radome and a tracking radar in a radome on the inlet bulkhead. The pitot tube was relocated to the right wingtip. The cockpit was larger to accommodate the radar display and control systems. After trials, the interceptor variant entered production in 1955 as the MiG-19P and went into service mostly with the PVO, though the VVS and even the Red Navy operated a number of them. It was assigned the NATO reporting name of Farmer-B.

Aside from the new radar nose, revised cockpit, and deletion of the fuselage cannon, the MiG-19P was similar to the MiG-19S, with the long tailfin fillet and all-moving tailplane. It was a bit draggier than the MiG-19S and performance suffered slightly; Soviet pilots had not been all that happy with the MiG-19S, and they were in general even less happy with the MiG-19P, not merely because of the slight degradation in performance, but also because the view from the radar-equipped cockpit was substantially worse, and because of the unreliability of the radar.

Early production MiG-19Ps had NR-23 cannon, but production then moved to NR-30 cannon. Farmer-Bs often carried a single unguided rocket pod under each wing for air-to-air attacks. Late in their service lives, some MiG-19Ps were modified to carry the K-13 / AA-2 Atoll Sidewinder AAM clone on a new outboard pylon. Late production machines had the improved RP-5 Izumrud radar, with greater range and better reliability. A number of MiG-19Ps were fitted with the Gorizont-1 ground-control datalink, which provided guidance information to direct a fighter to a target, and were redesignated MiG-19PG.

AAMs were seen as the future for fighter combat in the mid-1950s, and in 1956 work began on a missile-armed variant of the MiG-19P. Two of the MiG-19P prototypes were modified for trials, and the new variant entered service in 1957 as the MiG-19PM. The variant was assigned the NATO reporting name of Farmer-E.

The MiG-19PM was very similar to the MiG-19P, except that the cannon armament was removed, to be replaced by four K-5M / RS-2 / AA-1 Alkali beam-riding missiles. The RP-1 Izumrud radar was upgraded to the PR-2U variant, which provided control capabilities for the AAMs. The MiG-19PM was even more disliked than the MiG-19P, since the draggy missiles cut into performance substantially, and the K-5M AAMs were nothing to write home about as armament.

A few MiG-19Ps were modified to a MiG-19PM standard, though these aircraft could only carry two AAMs. A number of MiG-19PMs were fitted with the «Lazur” (Prussian Blue) ground control datalink in the 1960s. These modified machines were redesignated MiG-19PML.

The American attempts to use balloons to spy on the USSR led the Kremlin to task the Mikoyan OKB with developing a variant of the MiG-19 that could shoot down the balloons. Initial work focused on a lightened MiG-19S with reduced armament, no cockpit armor, no brake chute, and so on, fitted with uprated RD-9BF engines. The type was put into limited production in 1956 as the MiG-19SV, with one piloted by N.I. Korovushkin achieving a world altitude record of 20,740 m (68,044 ft) on 6 December 1956.

By this time, the US had obtained a much better reconnaissance platform than balloons, the Lockheed U-2 spyplane, which could cruise over the USSR at altitudes beyond the reach of any Soviet fighter, including the MiG-19SV. The first overflight of the USSR by a U-2 was on 4 July 1956, US Independence Day, as if taunting the Soviets, though in fact the Americans were surprised when Soviet radars spotted the machine, the belief being that the U-2 would be effectively invisible at its altitude to the radars the Soviets possessed. Shooting the U-2 down was a high priority, and so the Mikoyan OKB investigated fitting the MiG-19S with a liquid-fuel rocket booster. The result was the MiG-19SU.

The liquid-fuel booster was carried as a pack on the belly. Ground clearance was narrow and so take-off rotation had to be shallow. The pack was self-contained, requiring only electrical and mechanical attachment connections to the aircraft, but some airframe reinforcement was needed to handle the thrust stresses. The rocket worked well as far as that went, but storable liquid propellants as a rule are corrosive and toxic, and storable fuel and oxidizer generally have the interesting feature of catching on fire spontaneously when mixed together. That made the rocket pack somewhat troublesome and dangerous to deal with.

The MiG-19SU could indeed reach the operating altitude of a U-2; the problem was that it couldn’t really do very much once it did. At such altitudes, even the U-2, with its sailplane wings and light airframe, was barely aerodynamic, on the edge of stalling, and only the very best pilots could fly the thing. The MiG-19SU was about as aerodynamic and controllable as a brick once it reached such altitudes, and the turbojets were likely to flame out in the thin air. All a Red pilot could do was basically take a running jump up towards a U-2 from lower altitude, and hope he could score a few hits before the fighter reached the top of its arc and fell (or more likely tumbled) back down again.

A number of MiG-19Ps were also built to carry the rocket pack, being designated MiG-19PU. They weren’t any more effective, and the real answer to the U-2 was the new high-altitude S-75 Tunguska (NATO SA-2) SAM. SA-2s finally shot down a U-2 on the appropriate date of 1 May 1960, the pilot, CIA operative Francis Gary Powers, being captured. US President Dwight Eisenhower, who had always had misgivings about the overflights, canceled them for good.

The Czechs built a relatively small quantity of MiG-19S day fighters at the Vodochody plant from 1958 into 1961, with these machines designated Avia S-105. Only the airframes were actually built by the Czechs, with engines and other assemblies imported from the USSR. All S-105 production was retained for Czech service.

The Red Chinese would take ownership of the MiG-19 from the Soviets, but the Chinese got off to a slow start. Initial efforts at license production focused on the MiG-19P interceptor, with the Shenyang factory obtaining knockdown kits of the aircraft from the USSR in 1958, with the first Chinese-assembled machine flying in December of that year. The first Shenyang-built MiG-19P or J-6 flew in September 1959.

The Nanchang factory also worked on assembly and production of the MiG-19PM in parallel, with the aircraft to be designated J-6B, but the whole effort at both factories then fell down during the period known as «Great Leap Forward» that was driven by revolutionary rhetoric instead of rational industrial planning. The results were a fiasco, with programs pushed ahead unrealistically until they all collapsed in chaos.

After the collapse, Chinese industry picked itself up again and started over. Work on license-production of the MiG-19S day fighter at the Shenyang factory began in 1961, with the first Chinese-built machines flying at the end of the year. They retained the J-6 designation.

Production began to ramp up over the next few years, despite the fact that relations between China and the USSR deteriorated so badly in the early 1960s that the Soviets yanked all their technical assistance. Unfortunately, just as production was getting on track in mid-decade, China then entered into another period of confusion, this time caused by Mao Zedong’s «Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution».

The production of the MiG-19S / J-6 managed to survive, and in the 1970s production ramped back up again. By that time it was basically an obsolete aircraft, but for the moment the Chinese didn’t have the expertise to build a better one, and relations with the USSR remained frosty. The Shenyang factory built about 3,000 J-6s fighters into the 1980s, with large numbers exported under the designation of F-6 to Chinese client states, particularly Pakistan.

The most distinctive Chinese-built variant was the JJ-6 trainer, known as FT-6 for the export market. As the J-6 became the standard day fighter for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), the MiG-17 derived JJ-5 became increasingly inadequate, and so work was performed to design a tandem-seat variant of the J-6C as a supersonic advanced trainer. It was strictly a Chinese aircraft; formally speaking, there was never a MiG-19UTI.

The fuselage was stretched 84 cm (33 in) forward of the wings to accommodate the tandem-seat cockpit, which featured twin canopies that hinged open to the right. The wing cannon were deleted, but the fuselage cannon was usually retained; the single ventral fin was traded for twin fins.

Pakistan received a good number of FT-6 trainers, and in the 1980s set up a facility with Chinese help to refurbish them. The Pakistanis fitted their F-6s and FT-6s with Martin Baker Mark 10L rocket-boosted zero-zero (zero speed zero altitude) ejection seats. The Martin Baker seats not only improved safety, they also had a lower profile and gave more headspace in the cockpit. Another Pakistani innovation was fit of US-built AIM-9 Sidewinder AAMs on outer wing pylons. Pictures exist of the F-6 with this fit; it is unclear if the FT-6 was ever similarly equipped.

The F-6 is now out of production; while it appears to linger in service with Chinese client states, Chinese single-seaters have mostly been converted to drones, not just target drones, but attack drones as well, capable of performing air strikes.

The MiG-19’s service in Soviet colors was transitory and not very significant. The most action they saw was against Western snooper aircraft probing around or into the USSR’s borders. Possibly one of the best-known encounters was on 1 June 1960, when MiG-19 fighters shot down a Boeing RB-47H electronic reconnaissance aircraft that was snooping around Archangel in the north, with four of the crew killed and two taken prisoner. The RB-47H was in international airspace, but the Soviets were annoyed at U-2 and other incursions over their territory and wanted to send a message to President Eisenhower; the two prisoners were released after Eisenhower left the presidency. There were other shoot-downs by MiG-19s well into the decade.

The type was out of first-line service with the VVS and PVO by the end of the 1960s, though it lingered in secondary service well into the 1970s. Of course, by the time the MiG-19 was out of Soviet service, it was still a mainstay of the Red Chinese, and saw a bit of combat in Chinese colors. Taiwanese aircraft were common adversaries. There was a big air battle between Red and Nationalist Chinese forces in 1967, with twelve J-6s taking on four Lockheed F-104 Starfighters. The MiGs got the worst of it, with two losses and no kills.

There are also tales of Chinese J-6s flying combat missions during infrequent border squabbles with the Soviets, though with no records of dogfights; and of encounters during the Vietnam War with US aircraft that strayed into Chinese airspace. These confrontations resulted in a few shootdowns of Americans and, it seems, no losses of Chinese planes, though the MiGs sometimes had to make a hasty retreat back into Chinese airspace when the Americans called in reinforcements.

F-6s were supplied to North Vietnam late in the war, though the type didn’t see much action compared to the MiG-21 and particularly the MiG-17. North Vietnamese F-6s did perform a few dogfights in 1972, the last year of the real air war. It threw a curve at the Americans, being more agile than the MiG-21, but having better performance than the MiG-17.

The MiG-19 saw some combat in the Middle East, with Egypt obtaining their first batch in 1958 and Syria receiving the type beginning in 1962. Egyptian MiG-19s saw some action in the ground-attack role in support of revolutionary forces during the civil war in Yemen during the early 1960s. The first reported air combat in the Mideast with the MiG-19 was on 29 November 1966, when two Egyptian MiG-19 fighters tangled it up with two Israeli Mirage IIICs. The Israelis claimed two kills and no losses to themselves.

Many MiG-19s were in service with Egypt and Syria during the Six-Day War in 1967, but most were destroyed on the ground, and those that did survive were blown out of the sky by Israeli air superiority. Despite the unequal contest, Israeli pilots did find the MiG-19 a potentially dangerous adversary because of its performance, maneuverability, and heavy armament.

The Iraqis obtained some MiG-19S fighters in the early 1960s, but later sold them off; some did see action against the Kurds in the 1970s. In 1983, during the Iran-Iraq War, the Iraqis obtained a batch of F-6s through Egypt, while the Iranians acquired a batch of their own F-6s. Neither side made much use of them during the conflict, and there are no records of MiG-on-MiG dogfights.

The most significant combat seen by the MiG-19 was during the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971. The Pakistanis claimed that their F-6s shot down about ten Indian aircraft, with a loss of four F-6s. Of course, the Indians maintain that the Pakistani claims for kills are inflated and the number of losses are understated. In any case, the Pakistanis felt the F-6 had acquitted itself well and expanded their fleet. During the Afghan War, Pakistani F-6s would scramble to deal with incursions of Soviet and Afghan aircraft into Pakistani airspace. The intruders were often in pursuit of Mujahedin guerrillas who were trying to escape back to their sanctuaries in Pakistan; since it was an open secret that the Pakistanis were supporting the Mujahedin, sometimes the intruders didn’t feel like leaving when they were challenged, and there are tales of wild air battles. The Pakistanis didn’t retire the F-6 until 2002.

The F-6 was supplied to a number of African nations. Tanzania flew the type against Uganda during the war between the two states in 1978 and 1979, while the Sudan used it against separatists in southern Sudan, with at least one shot down. The Somalis flew the F-6 against rebels and the Ethiopians in the 1980s, though with the breakdown in civil order in Somalia all their aircraft ended up derelict by the early 1990s.

FUENTES Y REFERENCIA – SOURCES & REFERENCE

airvectors.net

Ugolok Neba

©jmodels.net

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.