| DATOS TÉCNICOS | TECHNICAL DATA |

| TIPO:Transatlántico. | TYPE:Ocean liner. |

| CONSTRUCTOR:Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. | BUILDER:Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. |

| BOTADURA:23 de junio de 1951. | LAUNCHED:23 June 1951. |

| DESPLAZAMIENTO:48.000 toneladas. | DISPLACEMENT:47,264 tons. |

| ESLORA:302 m. | LENGTH:990 ft. |

| MANGA:30,9 m. | BEAM:101.5 ft. |

| PUNTAL:9,86 m. | DRAUGHT:32.4 ft. |

| VELOCIDAD MÁX.:35 nudos (65 km/h). | MAX. SPEED:35 kn. (74.80 mph.). |

PROPULSIÓN:

|

PROPULSION:

|

| TRIPULACIÓN:900 (+1.928 pasajeros). | CREW:900 (+1,928 passengers). |

| CONSTRUIDOS:1 | BUILT:1 |

Los dos grandes transatlánticos Queen Mary y Queen Elizabeth contribuyeron durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial al esfuerzo bélico transportando grandes cantidades de fuerzas por todo el mundo, con un total de 320.000 desde América del Norte hasta Europa solamente. Sin duda, tal transporte era valioso en caso de guerra, por lo que el gobierno, en un esfuerzo conjunto con United States Lines, decidió encargar un transatlántico que se convertiría en uno de los más espléndidos que jamás haya surcado los mares. Un transatlántico que por primera vez en un siglo haría participar a los estadounidenses en la carrera por el Atlántico Norte.

El gobierno estadounidense estableció tres condiciones, y el barco tendría que cumplirlas en todos los puntos. La embarcación tendría que ser rápida, segura y fácil de convertir en transporte militar. La tarea de construir el nuevo transatlántico fue asignada a Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company en Virginia, todo supervisado por el arquitecto naval William Francis Gibbs. Durante las últimas tres décadas había estado soñando con un transatlántico de 1.000 pies capaz de alcanzar altas velocidades, y estuvo a cargo cuando el transatlántico alemán Vaterland fue reconstruido como Leviatán después de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Además, ya había construido barcos como el Malolo y el América. Pero esta fue la primera vez que se le dio prácticamente las manos libres para construir el mejor transatlántico de todos los tiempos. La quilla de su futura obra maestra se colocó el 8 de febrero de 1950.

El nuevo barco fue bautizado el 23 de junio de 1951, y el nombre que se le dio no podía dejar de despertar el orgullo nacional del pueblo estadounidense. Se llamaba United States. Para darle la gran velocidad que se requería, Gibbs había instalado turbinas enormes originalmente destinadas a portaaviones en su creación recién nacida. Y para cumplir con los otros dos requisitos de seguridad y rápida convertibilidad, Gibbs había optado por darle a su embarcación un tipo de diseño interior nuevo y más simple. Casi obsesionado con crear un barco completamente a prueba de fuego, Gibbs había tenido cuidado de no utilizar materiales inflamables al equiparlo. El United States era un barco de vidrio, acero, materiales sintéticos y aluminio. Los muebles, pasamanos y tumbonas fueron todos de aluminio. Gibbs incluso se acercó a Steinway Company con la sugerencia de que proporcionarían un piano de aluminio para los Estados Unidos, pero se negaron rotundamente a hacerlo. Al final se dijo que la única madera que se pudo encontrar a bordo del United States era la del piano y la del carnicero. Pero ningún pasajero podía quejarse de la comodidad del barco.

Los interiores simples también hicieron que la posible conversión en un buque de transporte de tropas fuera una tarea fácil. En comparación con los barcos más antiguos, que podrían tardar hasta tres meses en convertirse, el United States podía convertirse en un buque capaz de transportar 15.000 soldados en cuestión de días. Como había sido el gobierno quien exigió estas características, pagaría casi el 70 por ciento del costo total del barco, que terminó en 78 millones de dólares.

Con una longitud de 990 pies, el United States fue el barco estadounidense más largo jamás construido. Tenía una manga un poco más pequeña que los dos Queen, pero esto tenía su propósito. Con 101 pies de ancho, podría atravesar el Canal de Panamá, algo de lo que los dos transatlánticos gigantes de Cunard no podían hacer. Este también fue un requisito inicial en caso de que alguna vez fuera necesario. En realidad, el United States nunca serviría como transporte militar, aunque estuvo en espera durante la crisis de los misiles en Cuba en 1962.

Pero el mundo recordaría sobre todo al nuevo United States por una cosa, su gran velocidad. Durante sus pruebas de mar de seis semanas de duración, promedió unos fantásticos 38,25 nudos. Yendo a la inversa, el buque podía mantener fácilmente unos buenos 20 nudos. Todo gracias a sus turbinas Westinghouse que le proporcionaron unos asombrosos 240.000 caballos de fuerza. Pero debido al posible papel militar del barco, estas cifras se mantuvieron en secreto y no se hicieron públicas hasta 1978. No obstante, era incuestionable que el viaje inaugural del United States sería un récord.

El transatlántico estuvo a la altura de estas altas expectativas cuando el 3 de julio de 1952 zarpó de su muelle en Nueva York en su viaje inaugural con destino a Le Havre y Southampton. Al llegar a Bishop’s Rock, había promediado unos asombrosos 35,59 nudos y, por lo tanto, había rebajado diez horas y dos minutos al récord de 14 años del Queen Mary. Cuando se le entrevistó sobre su logro, el comandante del United States, el comodoro Harry Manning, dijo que en realidad solo había estado navegando con su barco con normalidad durante la travesía récord. Los periodistas británicos, todavía dolidos por la pérdida del título del Queen Mary, inmediatamente lo llamaron «fanfarrón yanqui».

Pero el comodoro Harry Manning no se jactaba. Durante su viaje inaugural, el United States solo había utilizado dos tercios de su potencia total. Si hubiera estado navegando a toda velocidad durante todo el viaje, el margen sobre el antiguo récord del Queen Mary habría sido indiscutiblemente mucho mayor.

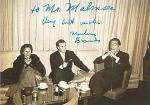

El buque disfrutó de una popularidad inmediata, y se le denominaba cariñosamente ‘The Big U’. Durante la década de 1950, la mayoría de los viajeros transatlánticos eran estadounidenses, y el hecho de que el United States fuera el único transatlántico estadounidense a menudo significaba que elegían cruzar con él. A pesar de sus interiores algo fríos y sencillos, representó la nueva generación de transatlánticos y muchas personas pronto lo tuvieron como su barco favorito, entre ellos el Duque y la Duquesa de Windsor que anteriormente habían favorecido a los dos Queen. Otro viajero habitual era Cary Grant.

Los Queen se enfrentaban a un rival de su talla. Esta competencia continuó durante la década de 1950, pero cuando comenzó la siguiente década, un nuevo competidor entró en lel cruce del Atlántico Norte. Con la introducción del avión a reacción, los pasajeros ahora tenían la oportunidad de cruzar el Atlántico Norte a una velocidad de 500 nudos en solo seis a ocho horas. Ni siquiera el veloz United States podía resistir velocidades tan grandes. Como todas las demás líneas navieras transatlánticas, United States Lines sufrió una gran pérdida de dinero. Ciertamente, las cosas no fueron más fáciles cuando los sindicatos de tripulantes comenzaron a exigir salarios más altos para sus miembros. Como resultado de estos problemas, y para generar ganancias adicionales, United States Lines comenzó a utilizar su buque insignia para un propósito para el que nunca había sido diseñado: realizar cruceros. En 1961, el Congreso de EE.UU. permitió que el buque realizara cruceros fuera de temporada, y estableció el primero el 20 de enero de 1962. Fue un crucero de 14 días desde Nueva York y los puertos de escala incluían Nassau, St. Thomas, Trinidad, Curazao y Cristóbal con una tarifa mínima de 520 dólares.

En 1964, su homólogo América fue vendido a Chandri Lines por 4.250.000 dólares. El United States se mantuvo en servicio, pero perdía millones de dólares cada temporada, y para 1969 había consumido más de cien millones de dólares en subsidios gubernamentales. La situación era insoportable.

El 25 de octubre de 1969, después de haber realizado unas 400 travesías con un total de 2.772.840 millas, el comandante, Capitán John S. Tucker, recibió un mensaje inalámbrico en el que se le explicaba que el crucero de otoño programado sería cancelado y que debía partir para una revisión adelantada. Como muchos seguramente sospecharon, este fue en realidad el principio del fin para el United States.

Y así fue. A fines de 1969, fue atracado definitivamente. El transatlántico quedó bajo la autoridad de la Administración Marítima Federal de los EE.UU. en 1973. Como la mayor parte de su construcción había sido un secreto de estado, se estipuló que nunca podría venderse a intereses no estadounidenses. Por lo tanto, el barco permaneció en Virginia.

Hacia fines de la década de 1970, el magnate naviero noruego Knut Kloster, líder de Norwegian Caribbean Cruise Lines, se acercó a los estadounidenses con una oferta para comprar el Big U. Estaba buscando un barco grande para convertirlo en un crucero, pero al final la oferta fue rechazada. Posteriormente, compró el desafortunado France, que luego se reencarnó con éxito como el crucero Norway.

Pero en 1978, una empresa estadounidense tuvo la misma idea. United States Cruises Inc. de Seattle compró el barco por la suma de 5 millones de dólares. El hombre detrás de todo, Richard H. Hadley, tenía grandes planes para el United States. Tenía la intención de darle un reacondicionamiento extenso de 150 millones de dólares y darle una vida completamente nueva como crucero. Aunque recorrió un largo camino con sus planes, e incluso firmó contratos con astilleros para realizar el acondicionamiento, de alguna manera los planes nunca se concretaron y United States Cruises Inc. decidió que el gran barco se vendería al mejor postor.

La oferta más alta otorgada fue de 2.600.000 dólares del presidente de Commodore Cruise Lines, Fred Mayer. En cooperación con un astillero turco en Estambul, Mayer tuvo una idea interesante que incluía a la legendaria Cunard Line. Se acordó que después de que el United States hubiera sido reformado en Estambul, Cunard lo operaría como compañero del Queen Elizabeth 2. Al igual que el QE2, el Big U serviría en la ruta del Atlántico Norte durante el verano, para pasar los meses de invierno como crucero. De repente, el futuro parecía mucho más brillante para el barco.

Todo dicho y hecho, el United States fue remolcado desde los EE.UU. a Estambul en junio de 1992. Pero, una vez más, la situación financiera se había sobreestimado en gran medida. Nunca se brindó la asistencia gubernamental esperada y se suspendieron los trabajos. Más tarde, Cunard explicó que ya no estaban interesados en operarlo. Consideraban que el QE2 era suficiente. Y así, el Big U permaneció en Estambul, y parecía que eventualmente sería vendido como chatarra.

Sin embargo, en 1996 fue remolcado nuevamente a los EE.UU., esta vez a los astilleros navales de Filadelfia. Nuevamente se esperaba que lo reacondicionaran, pero como tantas veces antes, el apoyo financiero esperado no se materializó.

El United States quedó inactivo en su muelle, esperando su futuro incierto. Sin embargo, fue incluido en el Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos en junio de 1999. Esto, en combinación con el arduo trabajo realizado por la fundación ‘Save the United States‘, generó un poco de esperanza en la continuación de la carrera del barco, aunque fuese ‘solo’ como hotel flotante o centro de conferencias.

Pero nadie podría haber imaginado el repentino y sorprendente giro de los acontecimientos en 2003, cuando Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) compró el barco con la intención oficial de restaurarlo por completo y dedicarlo a su servicio de pasajeros a Hawái con bandera estadounidense. La noticia sorprendió a la comunidad marítima, pero al mismo tiempo dio esperanzas de que el United States fuera rescatado de la misma manera que lo habían sido el France y el Norway. En agosto de 2004, NCL llevó a cabo estudios de viabilidad y, en mayo de 2006, el presidente de Star Cruises (propietaria de NCL) anunció abiertamente que el siguiente proyecto de la compañía era su restauración.

En marzo de 2010, se informó que se estaban aceptando ofertas por el barco, para ser vendido como chatarra. Norwegian Cruise Lines, en un comunicado de prensa, señaló que había grandes costos asociados con mantener a flote al transatlántico en su estado actual (alrededor de 800.000 dólares al año) y que, dado que SS United States Conservancy no pudo presentar una oferta por el barco, la empresa buscaba activamente un «comprador adecuado». Para el 7 de mayo de 2010, SS United States Conservancy había recaudado más de 50.000 dólares.

En noviembre de 2010, TNC anunció un plan para desarrollar un «complejo frente al mar de usos múltiples» con hoteles, restaurantes y un casino a lo largo del río Delaware en el sur de Filadelfia. Sin embargo, el acuerdo pronto fracasó, cuando el 16 de diciembre de 2010, la Junta de Control de Juegos votó para revocar la licencia del casino.

TNC finalmente compró el United States a NCL en febrero de 2011 por 3 millones de dólares con la ayuda de dinero donado por el filántropo H.F. Lenfest. Las conversaciones sobre la posibilidad de ubicar el barco en Filadelfia, la ciudad de Nueva York o Miami, así como los nuevos proyectos para el transatlántico, continuaron durante algunos años, pero todo quedó en nada.

En octubre de 2015, SS United States Conservancy comenzó a explorar posibles ofertas para desguazar el barco. El grupo se estaba quedando sin dinero para cubrir el costo mensual de 60.000 dólares por atracar y mantener el barco. Continuaron los intentos de reutilizar el barco. Las ideas incluyeron el uso del buque para hoteles, restaurantes u oficinas.

El 4 de febrero de 2016, Crystal Cruises anunció que había firmado una opción de compra por el United States. Crystal cubriría los costos de atraque, en Filadelfia, durante nueve meses mientras realizaba un estudio de viabilidad para volver a poner el barco en servicio como crucero con base en la ciudad de Nueva York. El 5 de agosto de 2016, el plan se abandonó formalmente y Crystal Cruises lo atribuyó a los múltiples desafíos técnicos y comerciales.

El 10 de diciembre de 2018, SS United States Conservancy anunció un acuerdo con la firma immobiliaria RXR Realty, de la ciudad de Nueva York, para explorar opciones para restaurar y reconstruir el transatlántico. En 2015, RXR había mostrado su interés en convertir un transatlántico fuera de servicio en hotel y lugar de eventos en el Muelle 57 de Nueva York. SS United States Conservancy imponía que cualquier plan de remodelación conservase el perfil y el diseño exterior del barco, e incluyera aproximadamente 2.323 metros cuadrados para un museo a bordo.

En marzo de 2020, RXR Realty anunció sus planes para reutilizar el transatlántico como espacio cultural y alojamiento de 55.740 metros cuadrados con amarre permanente, solicitando el interés de varias ciudades importantes de EE.UU., como Boston, Nueva York, Filadelfia , Miami, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Ángeles y San Diego.

The two great Queens ocean liners (Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth) had during World War II contributed to the war effort by transporting vast amounts of forces across the globe, with a total of 320,000 from North America to Europe alone. Such transportation was doubtlessly valuable in the event of war, so the government, in joint effort with the United States Lines, decided to order a liner that would become one of the most splendid ones that has ever sailed the seas. A liner which would for the first time in a century enter the Americans in the race on the North Atlantic.

The American government set up three conditions, and the ship would have to meet these at all points. The vessel would have to be fast, safe and easy to convert into a trooper. The task of building the new liner was given to the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company in Virginia, all supervised by the master naval architect William Francis Gibbs. For the last three decades he had been dreaming of a 1,000-foot liner capable of high speeds, and he had been in charge when the German liner Vaterland was rebuilt into the Leviathan after the First World War. Furthermore, he had already constructed ships like the Malolo and the America. But this was the first time he was given practically free hands to build the finest ocean liner ever. The keel of his future masterpiece was laid down on February 8, 1950.

The new ship was christened on June 23rd 1951, and the name she was given could not fail to awake national pride with the American people. She was called the United States. To give her the great speed that was called for, Gibbs had installed massive turbines originally intended for aircraft carriers in his newly born brainchild. And in order to meet the other two requirements of safety and quick convertibility, Gibbs had chosen to give his vessel a new, simpler type of interior design. Almost obsessed of creating a completely fireproof ship, Gibbs had been careful to use no flammable materials when fitting her out. The United States was a ship of glass, steel, synthetics and aluminium. Furniture, handrails and deckchairs were all made of aluminium. Gibbs even approached the Steinway Company with a suggestion that they would provide a piano of aluminium for the United States, but they totally refused to do so. In the end it was said that the only wood that could be found on board the United States was that in the piano and the butcher’s block. But no passenger could complain about the ship’s comfort.

The simple interiors also made the possible conversion into a troopship an easy task. Compared to the older ships, which could take up to three months to convert, the United States could be turned into a trooper capable of carrying 15,000 souls in a mere matter of days. Since it had been the government who demanded these features, they would pay almost 70 percent of the ship’s total cost, which ended up at $78,000,000.

With a length of 990 feet the United States was the longest American ship ever built. She had a slightly smaller beam than the two Queens, but this had its purpose. 101 feet wide, she could just make it through the Panama Canal, something the two giant Cunarders were not capable of. This was also a promise of quick troop transports, should any ever be necessary. Actually, the United States would never serve as a trooper, although she was put on stand-by during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

But the world would above all remember the new United States for one thing, her great speed. During her six weeks long sea trials, she averaged a fantastic 38.25 knots. Going in reverse, the United States could easily maintain a good 20 knots. All thanks to her Westinghouse turbines that provided her with an amazing 240,000 horsepower. But due to the ship’s possible military role, these figures were kept top secret and were not made public until 1978. Nonetheless, it was unquestionable that the maiden voyage of the United States would be a record-breaking, probably even a record-crushing one.

The United States truly lived up to these high expectation when on July 3rd, 1952, she left her pier in New York on her maiden voyage bound for Le Havre and Southampton. When arriving at Bishop’s Rock, she had averaged an astonishing 35.59 knots, and had thereby shaved ten hours and two minutes off the Queen Mary’s 14 year old record. When interviewed upon his achievement, United States‘ commander Commodore Harry Manning said that he had actually only been cruising his ship throughout the record crossing. British journalists, still sorry about the Queen Mary‘s lost title, immediately called him a ‘Yankee braggart’.

But Commodore Harry Manning was not bragging. During her maiden voyage, the United States had only used two thirds of her total power. Had she been going at full speed throughout the voyage, the margin to the Queen Mary‘s old record would unarguably been much greater.

The United States enjoyed immediate popularity, affectionately called ‘The Big U’. During the 1950s, the majority of transatlantic travellers were Americans, and the fact that the United States was the only American superliner often meant that they chose to cross on her. And despite her somewhat cold and simple interiors, she represented the new breed of ocean liners and many people soon had her as their favourite ship, among them the Duke and Duchess of Windsor who previously had favoured the two Queens. Another regular traveller was Cary Grant.

The Queens were faced with worthy rivals. This competition continued through the 1950, but as the next decade began, a new competitor entered the quest for the North Atlantic. With the introduction of the jet aeroplane, passengers now had the opportunity to cross the North Atlantic with a speed of 500 knots in just six to eight hours. Not even the swift United States could stand up to such great speeds. Like all other transatlantic shipping lines, the United States Lines now suffered great loss of money. Things were certainly not easier when the crewmember’s unions began demanding higher wages for their members. As a result of these problems, and to bring in some extra profit, the United States Lines began using their flagship for a purpose she had never been intended for, cruising. In 1961, the US Congress permitted the United States to do off-season cruises, and she set our on her first such on January 20th 1962. It was a 14-day cruise out of New York, and ports of call included Nassau, St. Thomas, Trinidad, Curacao, and Cristobal with a minimum rate of $520.

In 1964 the United States‘ running mate America was sold to the Chandri Lines for $4,250,000. The United States was kept in service, but she was losing millions of dollars every season, and by 1969 she had consumed over a hundred million dollars in government subsidies. The situation was unbearable.

On October 25th 1969, having performed some 400 crossings of a total 2,772,840 miles, the United States‘ commander Captain John S. Tucker received a wireless message in which it was explained that the ship’s scheduled autumn cruise would be cancelled and that she was to go to her builder for an early overhaul. As many surely suspected, this was actually the beginning of the end for the United States.

And so it was. In late 1969, she was laid up. The liner was put under the authority of the US Federal Maritime Administration in 1973. As the larger part of her construction had been a secret of the state, they explained that she could never be sold to any none-American interests. Therefore, the ship remained in Virginia.

Towards the late 1970s, Norwegian shipping magnate Knut Kloster, leader of the Norwegian Caribbean Cruise Lines, approached the Americans with an offer to buy the Big U. He was looking for a large ship to convert into a cruise ship, but in the end he was turned down. Subsequently, he instead purchased the unfortunate superliner France, which then was successfully reincarnated as the cruise ship Norway.

But in 1978, an American company had the same idea. The United States Cruises Inc. of Seattle bought the ship for the sum of $5,000,000. The man behind it all, Richard H. Hadley, had great plans for the United States. He intended to give her an extensive $150,000,000-refit and give her a completely new life as a cruise ship. Although he came a long way with his plans, and even signed contracts with shipyards to perform the refit. But somehow, the plans never really came to fruition, and the United States Cruises Inc. decided that the great ship would be sold to the highest bidder.

The highest bid given was $2,600,000, by Commodore Cruise Lines’ chairman Fred Mayer. In co-operation with a Turkish shipyard in Istanbul, Mayer had an interesting idea that included the legendary Cunard Line. It was agreed that after the United States had been refurbished in Istanbul, she would be operated by Cunard as a running mate to the Queen Elizabeth 2. Just like the QE2, the Big U would serve on the North Atlantc route during the summer, and spend the winter months as a cruise ship. Suddenly, the future looked a lot brighter for the United States.

All said and done, the United States was towed from the USA to Istanbul in June 1992. But once again, the financial situation had greatly been overestimated. The expected government assistance was never given, and work on the United States was called off. Later, Cunard explained that they were no longer interested in operating the United States. They felt that the QE2 was enough. And so, the Big U remained in Istanbul, and it looked as if she would eventually be sold for scrap.

However, in 1996 she was again towed to the USA, this time to the navy yards in Philadelphia. It was again hoped that she would be refitted, but as so many times before, expected financial support failed to materialise.

The United States lied idle at her pier, awaiting her uncertain future. She was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in June of 1999. This, in combination with the hard work done by the ‘Save the United States‘ foundation raised a little hope that there might just be some way for the United States to continue her career, albeit ‘just’ as a floating hotel or conference centre.

But no one could have imagined the sudden and surprising turn of events in 2003, when Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) purchased the ship with the official intent of fully restoring her to a service role in their newly announced, American-flagged Hawaiian passenger service. The news stunned the maritime community, but at the same time gave hopes of the United States being rescued in the same manner as the France and Norway had once been. In August 2004, NCL conducted feasibility studies regarding a new build-out of the vessel, and as late as in May 2006, the chairman of Star Cruises (which owns NCL) openly announced that the company’s next project is the restoration of the United States.

In March 2010, it was reported that bids for the ship, to be sold for scrap, were being accepted. Norwegian Cruise Lines, in a press release, noted that there were large costs associated with keeping United States afloat in her current state (around $800,000 a year) and that, as the SS United States Conservancy was not able to tender an offer for the ship, the company was actively seeking a «suitable buyer». By May 7, 2010, over $50,000 was raised by the SS United States Conservancy.

In November 2010, the Conservancy announced a plan to develop a «multi-purpose waterfront complex» with hotels, restaurants, and a casino along the Delaware River in South Philadelphia. However, the Conservancy’s deal soon collapsed, when on December 16, 2010, the Gaming Control Board voted to revoke the casino’s license.

The Conservancy eventually bought United States from NCL in February 2011 for a reported $3 million with the help of money donated by philanthropist H.F. Lenfest. Talks about possibly locating the ship in Philadelphia, New York City, or Miami as well as new projects for the liner continued for some years, but all came to nothing.

In October 2015, the SS United States Conservancy began exploring potential bids for scrapping the ship. The group was running out of money to cover the $60,000-per-month cost to dock and maintain the ship. Attempts to re-purpose the ship continued. Ideas included using the ship for hotels, restaurants, or office space.

On February 4, 2016, Crystal Cruises announced that it had signed a purchase option for United States. Crystal would cover docking costs, in Philadelphia, for nine months while conducting a feasibility study on returning the ship to service as a cruise ship based in New York City. On August 5, 2016, the plan was formally dropped, with Crystal Cruises citing the presence of too many technical and commercial challenges.

On December 10, 2018, the conservancy announced an agreement with the commercial real estate firm RXR Realty, of New York City, to explore options for restoring and redeveloping the ocean liner. In 2015, RXR had expressed interest in developing an out-of-commission ocean liner as a hotel and event venue at Pier 57 in New York. The conservancy requires that any redevelopment plan preserve the ship’s profile and exterior design, and include approximately 25,000 sq ft (2,323 sq. m.) for an onboard museum.

In March 2020, RXR Realty announced its plans to repurpose the ocean liner as a permanently-moored 600,000 sq ft (55,740 sq. m.) hospitality and cultural space, requesting interest from a number of major US cities including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Miami, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

FUENTES Y REFERENCIA – SOURCES & REFERENCE

greatoceanliners.com

Wikipedia

©jmodels.net

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.